Info︎

Queer Space:

Defining Public Spaces of Gay Male Sexuality and Desire in New York City in the Twentieth Century

Figure 01: Nude Sunbathers at the Greenwich Village Piers, 1975-86

Written for “Questions in Architectural History”

Spring 2019, Columbia GSAPP

Critic: Nader Vossoughian, Caitlin Blanchfield

Societal attitudes toward same-sex relationships, and the spaces these relationships occupy, have varied greatly over time and across place. However, the idea of a ‘homosexual as a person’ was defined in the Victorian era. Before that time, the sexual act and the person were not associated.1 When a person is labeled as homosexual, society is able to group these individuals together, examine their behaviors, and classify their existence. Subsequently, this classification provides implications on legislation, stigma, and the formation of exclusionary as well as inclusionary spaces. These inclusionary spaces, or queer space(s), can be defined as “spaces that critique the divisions of sexuality, gender, class, and race through political, cultural, social, real, ephemeral, geographic, and historical contexts.”2 Simply, they can be understood as a space where queer people are able to feel safe and thrive - a place with safety, comfort, and community. Throughout the past century, these spaces have taken on various forms within the urban context. Queer spaces of sexuality and male desire have been formed through the exploitation of legal loopholes as well as the reclaiming of abandoned, unwanted, and unwatched public spaces at both the urban and architectural scale. By taking advantage of the anonymity found in these public spaces, queer people, and specifically the gay male,3 have defined and continue to define spaces as their own within the context of New York City throughout the past century.

From an early point, young people in search of gay sex and romance in the city discovered that “privacy could only be had in the public.”4 As gay men came into the city, they sought places with the possibility of safety, comfort, and community. Somewhat counter-intuitive, claiming public space as queer space maintained a level of anonymity and safety in numbers in a hostile society. New York City’s streets, parks, and in some cases, entire neighborhoods served, and still serve to a lesser extent, as vital meeting grounds for men who lived with their families or in cramped quarters with few amenities. These public spaces became spaces where many men went for sex and ended up being “socialized into the gay world.”5

On an urban scale, the gay world evolved throughout the city, but it most developed in visible form in just a few neighborhoods. At the turn of the twentieth century, the Bowery was the epicenter of gay life, with young men participating in raucous nightlife, and socializing in the famous cafeterias of the area. However, by the 1920s, gay men quickly shifted their focus to Greenwich Village and Harlem, the most famous and exciting centers for gay life in New York City. The emergence of Greenwich Village as a gay center was “closely linked to the development of the bohemian community there,”6 making it a reasonably tolerant environment for queer individuals. Newcomers to the Village were attracted by its winding streets, Old World charm, and cheap rents due to its relative isolation from the rest of the city at the time. Above all, the social life and “particular forms of eccentricity” (Figure 02) made it easy for gay men to fit into society en masse by providing “a cover to those adopted flamboyant styles in their dress and demeanor.”7 The Village’s reputation for tolerating nonconformity made it a safe place for homosexuals to live and explore their sexuality out in the open view of the public, seizing the opportunity provided by the existing culture to begin building the city’s most famous gay enclave. However, despite the Village’s nationwide fame and popularity, many gay men themselves of the time regarded Harlem as the most exciting center of gay life in New York City. Because of segregational laws at the time, it was the only place where black gay men could congregate in commercial establishments. While it was “easier for white interlopers to be openly gay during their brief visits to Harlem than it was for the black men who lived there around the clock,”8 it was black gay queers that nonetheless turned Harlem into a homosexual mecca during the Roaring Twenties. Denied access to most of the segregated restaurants and spaces white gay men frequented in Greenwich Village, black gays and lesbians built an “extensive gay world in their own community, which in many respects surpassed the Village’s in scope, visibility, and boldness.”9 Most unique to Harlem was its nightlife. Though most of Harlem’s residents socialized as corner cabaret saloons, basement speakeasies, and tenement parties thrown to raise money for rent, the drag balls were what brought the entire city north. Most famous, the “Hamilton Lodge Ball” was a glamorous nightclub that “drew hundreds of drag queens and thousands of spectators”10 to see and be seen. Workingmen dressed in drag would perform and compete in front of the middle-class men and social elite (Figure 03), bringing together the wide range of people that were forced to live side-by-side into one queer space. Although potentially at a greater risk of assault and violence due to systemic racism in the criminal justice system, Harlem’s primary classification as a black neighborhood provided a level of inconspicuousness for gays of all races, creating a space where “more men were willing to venture out in public in drag”11 than anywhere else in the city.

Figure 02: Claude McRay and Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven, famous Bohemians of the 1920s VillageFigure 03: Queens Compete at a drag ball in the 1920s

On a smaller scale, gay men “took full advantage of the city’s resources to create zones of gay camaraderie and security”12 across program typologies within the hetero-centric built environment of public spaces. Bar-hotels at the turn of the century, Central Park’s Ramble during the 1950s, and the Greenwich Village Piers during the 1970s are all prime examples of the reclaiming of queer space in the twentieth century.

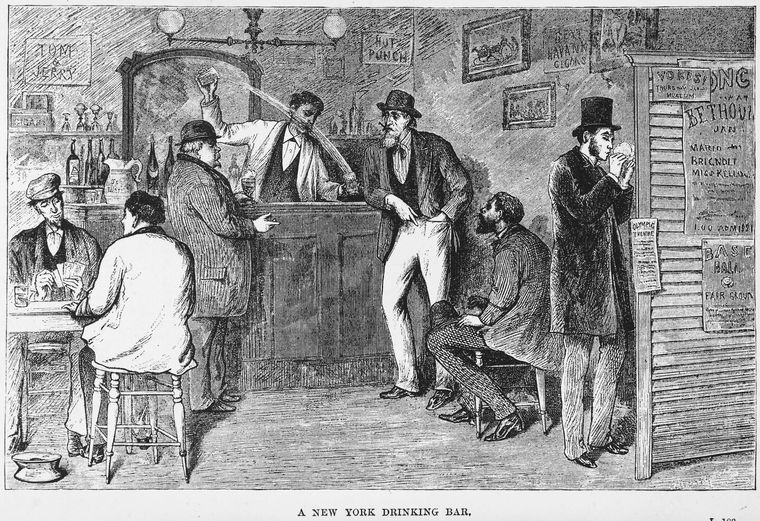

At the turn of the century, the state of New York passed the Raines Law, requiring saloons to close on Sunday in an effort to control working class male sociability and productivity. A small provision allowed bars attached to hotels to remain open, as they generally served a class of male drinkers considered more respectable to lawmakers than the typical working class citizen. In order to stay open, bars across the city began to offer rooms for rent as a part of their establishment. Unintentionally, prostitution rates within the city skyrocketed and spread to new neighborhoods. The government and neighborhood committees soon acted to close these ‘Raines Hotels’, and attempted to curb the rise of prostitution by prohibiting women from entering the establishments that they could not close. Always searching for space to occupy, queer men took advantage of the provision and began to utilize these hotel rooms as a safe space to exercise their sexuality. Essentially the first gay hotels in the city, business owners were willing to turn a blind eye and rent “rooms… to male couples on an hourly basis, about whose purposes they could have had no doubt”13 to remain open and fly under the radar of the restrictive laws (Figure 04). However, these small hotels and cabarets soon developed a citywide reputation among gay men, and by 1923 New York legislature “specified homosexual solicitation… as a form of disorderly conduct”14 - specifically and formally banning the assembly of gay people in a public space. Nevertheless, this practice of queer men claiming considerable space for themselves within the public realm continued through the remainder of the century, in increasingly public domains.

Figure 04: Depiction of men in a ‘Raines Hotel’ in New York City at the turn of the 20th century

By mid-century, “cruising” in the parks became one of the most popular and secure places to meet friends and search for sexual partners in the city. Central Park offered “vast stretches of unsupervised wooded areas”15

that became a vital social gathering space for gay men to have privacy in the public. Characterized as an intimate, secluded maze of intermingled trees and branches, winding walkways through man-tall thickets of bush, and a network of man-made trails into the densest foliage of the area, ‘The Ramble’ was an opportune space for gay men to socialize shielded from the view of even the highest buildings along Central Park West. “Confessional-like spaces created by the untrimmed wild fauna”16 and dark areas underneath bridges and arches were particularly available in this area of the park, leading to its claim as queer space around the clock. The West side of The Ramble’s 30 acre section of the park had a “reputation as a homosexual meeting ground”17 so popular that the lawn at the North end of the area was nicknamed “The Fruited Plain,”18 a play on one of the derogatory slang words used to describe gay men at the time. Men of all classes roamed this area of the park after work to socialize, which at this time of day was casual and friendly. However, as night approached, The Ramble was utilized by men searching for sex, with some of the most trafficked areas “crowded wall to wall with men until four in the morning”19 searching for an escape under the safety of the night. However, much like the Raines Hotels decades prior, congregating in The Ramble as a gay man was not without its own risks. Word of The Ramble and the activities taking place within it were soon discovered by authorities as well as homophobic citizens of the city. Although relatively infrequent, arrests and beatings occurred that not only inflicted physical harm, but could also cost a person their entire job and livelihood because of stigma associated with homosexuality in society. While this didn’t stop the practice of the queer sexualization of Central Park, gay men continuously sought new neglected and overlooked spaces to claim as their own, often resulting in seedier and abandoned areas of public space within the context of New York City.

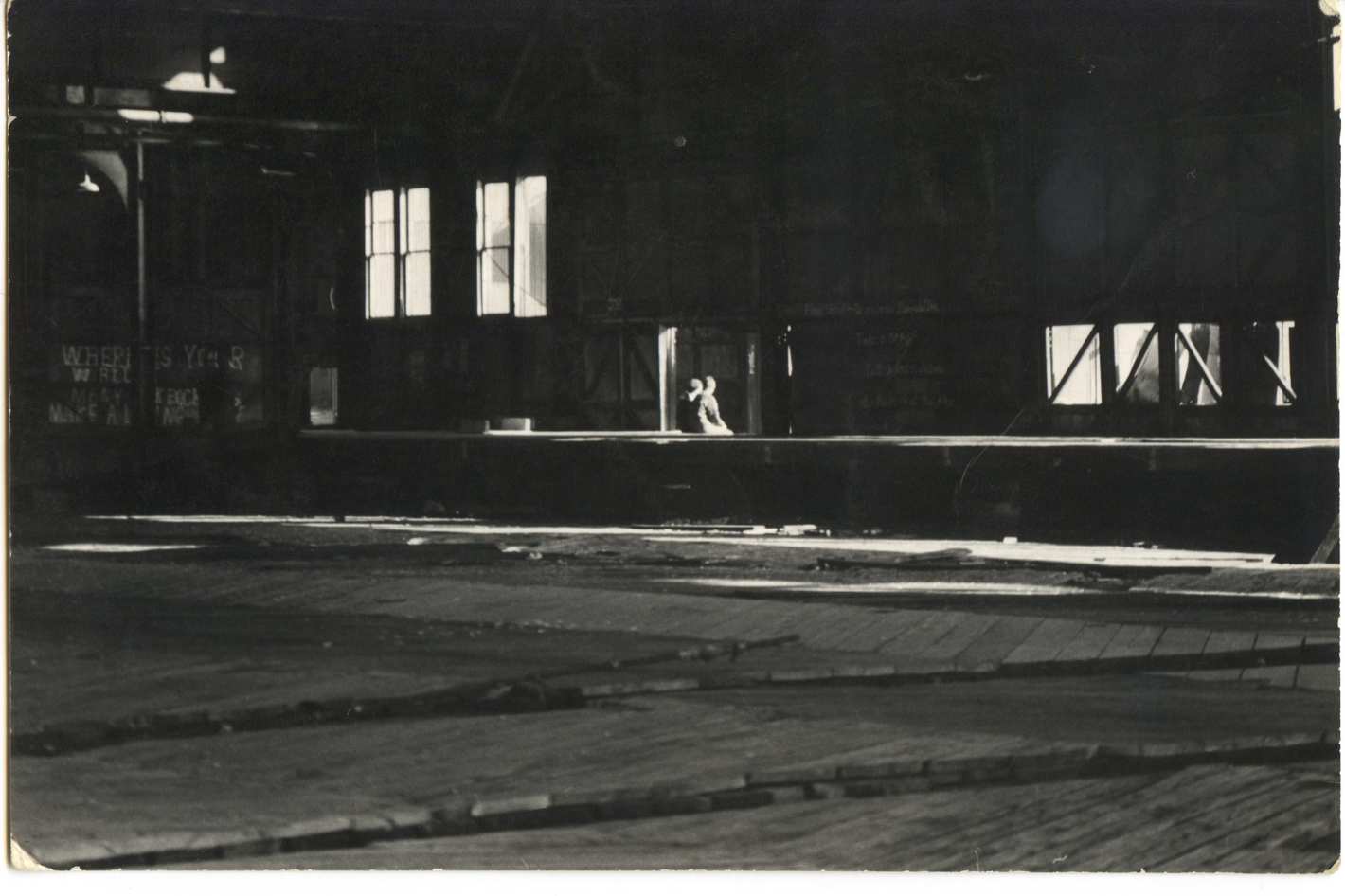

Already by the beginning of the first World War, the piers along Greenwich Village’s Hudson River waterfront were a popular cruising area for gay men. The concentration of unmarried and transient men, numerous bars in the area, and the construction of the West Side Highway in the 1930s separating the piers from the city established the area as one of the centers for gay life throughout the first half of the century. Eventually, innovations in the maritime shipping industry and growth of the airline transportation methods made the West side piers and shipping terminals obsolete, leading to their complete abandonment by the mid-1960s.20 When the West Side Highway was closed and left to decay in 1973 due to safety concerns,21 the area was reinforced as an un-policed backwater area for risky activity. The abandoned pier structures, specifically pier 45 at the end of Christopher Street (site of the infamous Stonewall Riots), were claimed by gay men and reinforced as a space to “sunbathe naked, cruise, and have public sex by the early 1970s”22 (Figures 05-07). Experienced as a “utopian world in suspension over the water’s edge”23 the queerness of the piers during the 1970s and 80s are indicative of the threshold between public and private space that gay men so typically occupied and appropriated as queer space in the city. Beyond sex, the piers also became a space for queer men, as well as women, to express themselves artistically. Symbolic of the “seeming collapse of modernity,”24 artists were attracted to the culture and dystopian nature of the piers, because they appeared to be out of control. The interior and exteriors of the piers’ decaying terminals became the site for art installations, murals, photography and performances by the likes of Vito Acconci, Peter Hujar, Alvin Baltrop, and David Wojnarowicz (Figure 08).25 These artists often inserted themselves into the pier culture, granting them a status as observers, documenters, and participants in the local queer scene. The infusion of art into the culture of the piers led to an increased sense of permanence and “place,” and expanded the cultural significance of the claiming of these spaces by queer individuals. The formation of queer space was still a reaction to the need for safety and a space to exercise sexual desire, but increasingly became a place to form a collective queer identity in the city. The Greenwich Village Piers were a fully fledged gay world within New York City. However, by the 1980s, the AIDS epidemic and planning for waterfront improvements began to impact the area and destroy the queer spaces that were formed. By the time that it was demolished in the mid-1980s, the Christopher Street Pier terminal “had become a safe haven and first or second home for many marginalized queer youth of color”26 who to this day make up a significant percentage of the homeless youth population in New York City. While most of the physical history of its LGBT past has been destroyed, the Greenwich Village Piers remain important public spaces for LGBT people today.

Figure 05: Two men sunbathe on one of the Greenwich Village piers along the Hudson River

Figure 06: Two men in an abandoned pier structure

Figure 07: Nude sunbathers en masse

Figure 08: Queer artist David Wojnarowicz paints a mural at Pier 34, 1983

The claiming of the internet as queer space is the ultimate allegation of public space by the gay male in the last one hundred years. While the internet contains space for groups of all kinds, the gay male has uniquely utilized the online platform to completely transform the way that the community interacts today through the invention of Grindr.27 A geo-social network, dating, and chat app invented in 2009, the app “provides a new mode of romantic experience” where finger scrolls replace physical touch (Figure 09), and “less than five percent of the conversations… end up in offline encounters.”28 When members do meet offline, the app is successful in accelerating homosocial and romantic encounters by eliminating the risk of approaching through a space where there are pre-agreed notions of community and expected behavior. In this way, people are able to inhabit this queer space “not only in the dark of bedrooms” or the types of public queer spaces aforementioned, they’re also occupying queer space “in offices, bars, streets, trains, factories, gyms, and college campuses” by turning on their phones.29 Grindr’s appropriation of queer space is everywhere and nowhere, neither fully virtual or physical, and exists as what queer space has always aimed to be - safe, comfortable, and community building.30 As a result, traditional cruising spots and dark rooms around the world have seen their community reduced sine the dawn of Grindr, as “younger generations have abandoned them for digital spaces to cruise and negotiate sex.”31 In New York City as well as across the world, gay bars are “closing down” as queer people are beginning to opt to “connect with people on social media and with location-based technology” in informal “pop-up or micro-sites” of queer space in the city32 instead of pre-established ones. The traditional spaces of queer community, “where queer men and women had to go to define themselves” are increasingly virtual and “are [no longer] necessary.”33 As an interface, Grindr has redefined what the notion of queer space looks like in New York City, and has questioned if queerness, architecture, and urbanism still intersect.

Figure 09: Grindr user interface on a mobile phone and smartwatch depicting the fifteen nearest acive users in real time. Users are encouraged to “tap” or “chat” with other users they’re interested in.

By taking advantage of the privacy found in the anonymity of public spaces, gay males have managed to claim abandoned, unwanted, and ignored spaces within the context of New York City as queer space throughout the past century. Although recent online platforms such as Grindr have continued to reinvent the degree of physicality and temporality of these spaces within the city, it is still apparent that the intersections between queerness, architecture, and urbanism still exist and are as prevalent and important as ever. In fact, in 2016, apartment towers in Chelsea (adjacent to Greenwich Village) and Harlem were among “Grindr users’ favorite locations to find lovers worldwide,”34 indicating that deeply established physical queer spaces still exist even as gentrification sets in. Furthermore, as gay rights continue to be attacked by government institutions and hate groups, non-sex-centric physical spaces of queer community building and safety are more important than ever. Debates regarding gender-specific bathroom use, housing discrimination based on sexuality, and the disproportionate population of queer homeless youth call forth architectural and urbanistic responses. In the era of gay pride and the public celebration of ones identity, it has become more and more common to be open and accepted as queer, especially in a city such as New York. Just as gay males claimed public space as their own throughout the last century, and queer people of all identities claim public space today, designers should continue to question the implications of space on queer individuals, and begin to design space, both physical and invisible, where queer people are able to feel safe and thrive for centuries to come.Footnotes:

1. Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978), 360

2. J. Matthew Cottrill, “Queering Architecture: Possibilities of Space(s)” (Master’s Thesis, Miami University, 2006)

3. For the purposes of this essay, only the experience of the gay male in New York City shall be discussed. However, many of the notable advancements and triumphs in the formation of queer space in New York City are owed to lesbian, bisexual, trans, and queer people outside or in tandem with the cis-gender gay male experience

4. George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Makings of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Perseus Books Group, 1994), 202

5. George Chauncey, IBID, 179

6. George Chauncey, IBID, 228

7. George Chauncey, IBID, 229

8. George Chauncey, IBID, 244

9. George Chauncey, IBID, 244

10. George Chauncey, IBID, 244

11. George Chauncey, IBID, 249

12. George Chauncey, IBID, 152

13. George Chauncey, IBID, 162

14. George Chauncey, IBID, 172

15. George Chauncey, IBID, 180

16. Doug Ireland, “Rendezvous in the Ramble,” New York Magazine, July 1987

17. Doug Ireland, IBID

18. Doug Ireland, IBID

19. Doug Ireland, IBID

20. "Greenwich Village Waterfront," NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, 2017, accessed May 08, 2019, http://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/greenwich-village-waterfront-and-the-christopher-street-pier/.

21. "Story Map Journal - A Utopia on Our Own Terms: Queer Encounters on the Chelsea Piers," Arcgis.com, accessed May 08, 2019, https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=4d7effb0d7494294a52c91ffd971638c#.

22. "Greenwich Village Waterfront," IBID

23. "Story Map Journal - A Utopia on Our Own Terms: Queer Encounters on the Chelsea Piers," IBID

24. "Story Map Journal - A Utopia on Our Own Terms: Queer Encounters on the Chelsea Piers," IBID

25. "Greenwich Village Waterfront," IBID

26. "Greenwich Village Waterfront," IBID

27. While Grindr was invented by and primarily used by gay males, it is geared towards gay, bi, trans and queer people. For the purposes of this essay, only the gay experience remains the focus.

28. Andrés Jaque. “Grindr Archiurbanism,” Log 41, no. 3 (2017): 77

29. Andrés Jaque, IBID, 77

30. Grindr has come under criticism for promoting unrealistic body image standards and not taking sufficient action to curb hate speech. Because these are issues plaguing most social media platforms, it does not seem relevant to this essay. Although the location data crucial to the function of the app has also been tragically used to track and arrest gay men in Egypt, this online queer space is safe in most countries around the world.

31. Andrés Jaque, IBID, 78

32. Aaron Betsky, interview by Jaffer Kolb, “The End of Queer Space?,” Log 41, no. 3 (2017): 88

33. Aaron Betsky, IBID, 88

34. Andrés Jaque, IBID, 79

© Alek Tomich_ New York, NY