Info︎

Let’s Have a Kiki

A Social Infrastructure for Black and Queer Individuals Living Within the Margins of New York, Paris, and Cape TownOngoing Study

+ 2021 William Kinne Fellows Traveling Prize Recipient

Independent Study

Let’s Have a Kiki is the first in a series of studies exploring the structural and spatial evolution of the Kiki scene beyond the Ballroom queer subculture. Characterized as a more informal youth-of-color-led faction of Ballroom, Kiki culture has successfully reduced homelessness and HIV in Black and Queer youth living in New York City due to its strong partnerships with non-profit and community-based organizations. As the culture spreads globally, houses reinvent social hierarchies and design infrastructures to fit the localized socio-political context. In cities with large populations of migrants and refugees living on the fringe of urban society, such as Paris and Cape Town, Kiki culture provides a conduit for Black and Queer African migrants to find community and safety outside of their oppressive home nations. Let’s Have a Kiki will focus on documenting and mapping the social and spatial network of Kiki culture across three urban centers. Key diagrams and collages will illustrate methodologies used by Kiki participants to adapt the New York model in establishing systems of visibility, collectivity, and support for Black and Queer youth living within the margins of society.

Figure 01 (Above): Members of the House of Mizrahi’s Paris chapter

Figure 02 (Below): Carsten Mizrahi celebrating his Sex Siren Grand Prize trophy at the 'Peoples Choice Awards Gala

Ballroom is an underground Queer subculture that originated in New York City, in which people compete for trophies and recognition at events known as balls. Attendees “walk” for specific categories to win prizes, mixing elements of performance, dance, vogue, lip-syncing, and modeling on the runway. Unlike formal queer spaces today, which typically occupy regulated environments such as bars and clubs, the sites of balls are placeless creations characterized by the temporary occupation of physical and virtual spaces whose meanings are co-opted from those which are ascribed to them (Rio UltraOmni 111). This versatility has contributed to Ballroom’s ability to continue and thrive to this day when many other forms of formalized queer social space have disappeared due to discriminatory urban regulations in the context of the HIV epidemic and the current COVID-19 global pandemic.

Throughout its history, ballroom participants were mainly Black and Latine members of the Queer community who routinely encountered racism within the greater drag pageantry circuit. In response, house culture within the ballroom scene was established in Harlem in 1972 by Crystal and Lottie LaBeija, Black queens of The Royal House of LaBeija, as an alternative competition format deeply catered to the intersectional Black and Queer experience. Houses compete in balls but concurrently serve as alternative families and non-heteropatriarchal systems of kinship, support, space, and care for queer youth communities prone to homophobic and transphobic violence and estrangement (Rio UltraOmni 88). These houses operate as a social rather than physical space where the housework exists within the member’s relationships with each other and emphasizes collectivity and refuge without relying on fixed spatial or capital entities (Bailey 23). Through house culture, the disenfranchised discover a collective identity and a safe place to belong.

The Kiki subculture within the New York house and ballroom scene arose during the last two decades from a need to create space for queer youth of color, many of whom were homeless and in desperate need of HIV prevention services. Young ballroom community members would informally congregate to socialize and prepare for the mainstream balls at health outreach organizations while also building connections and trust with community health and wellness providers. Through this system, the Kiki scene was born: a separate less-competitive sect of house culture that borrows from traditional Ballroom’s legacy and insists on a youth-of-color-focused grassroots leadership with support from local community-based organizations (Matthes and Salzman). Currently, the Kiki scene in New York City is even more active than the mainstream scene. It has been prolific in establishing successful partnerships with public and private entities to expand access to housing and HIV prevention services, testing, and counseling for Black and Queer youth.

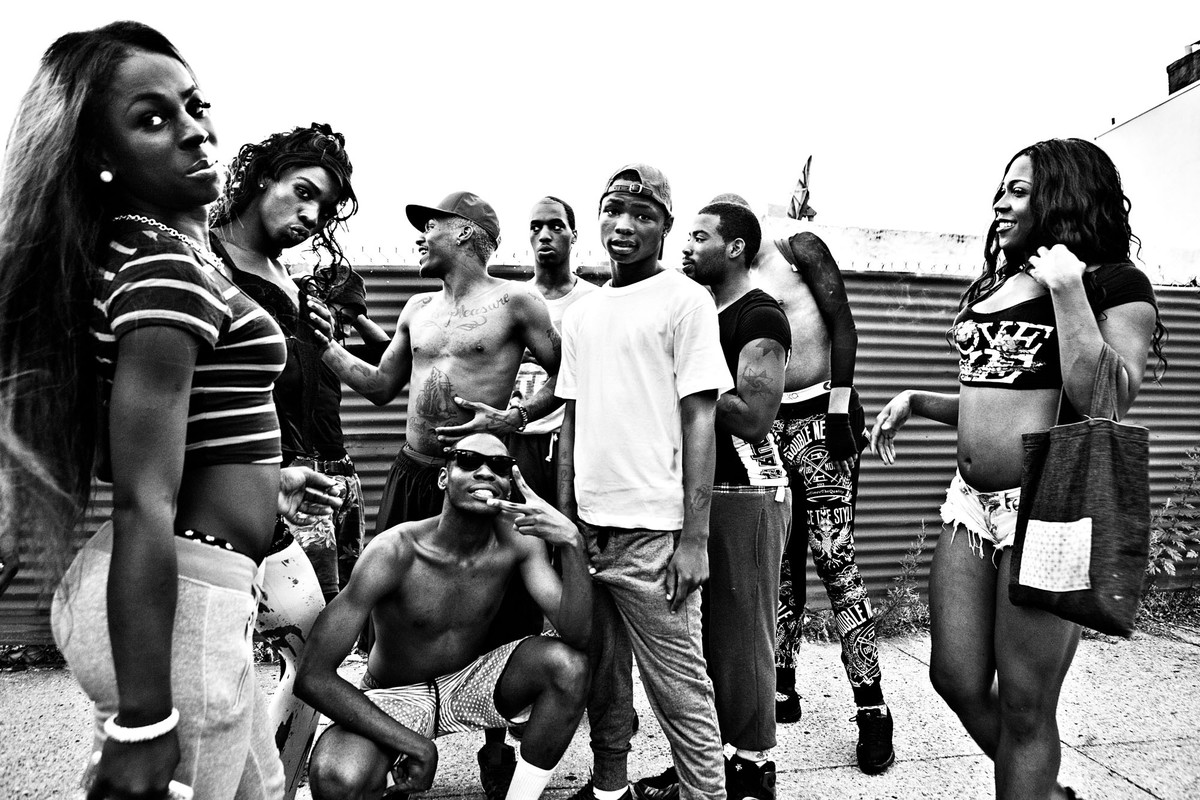

Figure 03 (Above): New York’s House of Bangy Cunt

Figure 04 (Below): Zay Wilder Walking in the Blackout Ball

Today, Ballroom and Kiki culture have reached an international following through films such as Paris is Burning, and television shows like Legendary, Pose, and Rupaul’s Drag Race. Houses have been established in cities worldwide, reinventing social hierarchies and infrastructures to fit the localized socio-political context. While housing instability and HIV prevention service needs among queer youth of color are universal across borders, the increase in sanctions among queer populations in many African nations has contributed to the rising number of queer migrants seeking asylum in friendlier environments. Using Paris and Cape Town as case studies, this research will examine how the non-spatial social infrastructures of the New York Kiki Ballroom scene have adapted spatially to these new urban contexts, serving as a means through which Black and Queer African migrants can find community and safety in cities outside of their oppressive home nations. The research will be completed in three phases:

The first phase will examine the New York origins of the Kiki subculture: mapping its formation, learning about its membership, and understanding the intricacies of the relationships between Kiki Houses and local community-based organizations providing support. Events such as The Annual Latex Ball, hosted by the House of Latex and the Gay Men’s Health Crisis organization, combine HIV and AIDS prevention information with Ballroom competition and provide a window into the overall impact of Kiki culture on Black and Queer youth in the city (Matthes and Salzman). Further, collectives of community-based organizations and non-profit agencies, such as the Kiki Coalition, have come together to provide community mobilization for youth and provide a blueprint for successful organizing that can replicate globally.

Additionally, throughout the pandemic, Kiki participants have taken to surrogate support systems, co-opting virtual platforms such as Zoom, Venmo, and OnlyFans to communicate, socialize, and maintain their livelihood. This new frontier invites an investigation into a Kiki-specific form of queer social urbanism that is simultaneously extremely public yet operates within a range of spatial environments that are entirely private. As many Black and Queer youth live in unfriendly conditions far from urban centers or with biological families that obstruct privacy, this contemporary condition may provide a model towards even greater inclusivity not yet afforded within the subculture.

The second phase will look to Paris, the home of the largest population of the African diaspora in Europe and a historical destination for North African migrants fleeing oppression. While the city is widely accepting of queerness, migrants and their families often live in the outskirts of city in the ‘banlieues’, away from the urban centers where Kiki culture thrives and within communities that largely mimic the homophobic attitudes of their country of origin (Hutchinson). The ballroom scene in Paris, now home to over fourteen Houses and considered the European mecca of Kiki, is in its third generation of members who are beginning to spread the ideas of the culture beyond the underground (Gaestel). This study will examine how French youth of color and community-based organizations adapt the New York model of Kiki culture to expand their non-spatial network of collective support and care to the Black and Queer migrant youth on the physical periphery of the city.

The last phase of research will move to Cape Town, South Africa. Like Paris, the city of Cape Town has been a frequent destination for migrants from neighboring southern African countries where homosexuality is largely illegal and sometimes punishable by death. Considered the gay capital city of Africa, the post-apartheid constitution of South Africa was among the first in the world to strictly outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation. However, the deeply embedded homophobia and racism in ethnic subcultures, combined with increasing xenophobia within the South African society, has made life difficult for these migrants, who often find themselves within the plains on the edge of the city far from queer social infrastructures and formalized space (Chikalogwe). Over the last three years, the Kiki scene has begun to proliferate underground within the South African Black and Queer community, reshaping the culture to cater to African bodies and customs (Collison). At this pivotal moment, this study will look at how the reinvention of Kiki culture to fit a uniquely African point of view has afforded an opportunity to create localized safe space and community, bridging the socio-political and physical gap for Black and Queer migrants living in or on the outskirts of Cape Town.

Let’s Have a Kiki will attempt to document and map the social and spatial network of Kiki across the urban centers of New York, Paris, and Cape Town. This project will produce a visual taxonomy of these visible and invisible infrastructures and diagram the relationships and methodologies that Kiki participants have used to form alternate urbanisms in response to crises, and establish systems of visibility, collectivity, and support to Black and Queer youth living within the margins of society.

Figure 05 (Above): Performer Winnie Wakanda Washington and ball organiser Treyvone Moo

Figure 06 (Below): Cape Town performers Queezy, Daniel Walton, Mziyanda Malgas, and Chester Martinez.

More coming soon, when it is safe to travel again.

Bibliography:

Bailey, Marlon M. “Butch Queens Up in Pumps: Gender, Performance, and Ballroom Culture in Detroit.” United States, University of Michigan Press, 2013.

Collison, Carl. “The Joburg Ballroom Culture Creating ‘Queer Utopia’.” New Frame, 21 Aug. 2019, www.newframe.com/the-joburg-ballroom-culture-creating-queer-utopia/.

Gaestel, Allyn. “‘Paris Is Burning’ Goes Global.” Edited by Eve Lyons, The New York Times, The New York Times, 29 June 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/06/29/style/paris-is-burning-queer-ballroom-culture.html.

Hutchinson, Kate. “‘Son of Immigrants, Black and Gay’: A D.J. Breaks Barriers in France.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 27 Aug. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/08/27/arts/music/kiddy-smile.html.

Matthes, Anja, and Sony Salzman. “In the Kiki Ballroom Scene, Queer Kids of Color Can Be Themselves.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 7 Nov. 2019, www.theatlantic.com/photo/2019/11/nyc-kiki-community/599830/.

Rio UltraOmni, Malcolm John. “Drag Hinge: ‘Reading’ the Scales between Architecture and Urbanism.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Department of Architecture, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019.

Image Credits:

Cover Image: Daniels, Meghan. Clip from ‘Historical Glitch.’ https://www.meghandaniels.com/#/historical-glitch/

Figure 01: Thierry, Dustin. “Members of the House of Mizrahi’s Paris chapter.“ ‘Paris is Burning’ Goes Global, The New York Times, 2019.

Figure 02: Thierry, Dustin. “Carsten Mizrahi.” ‘Paris is Burning’ Goes Global, The New York Times, 2019.

Figure 03: Matthes, Anja. Photograph of New York’s House of Bangy Cunt. In the Kiki Ballroom Scene, Queer Kids of Color Can Be Themselves, The Atlantic, 2015.

Figure 04: Matthes, Anja. Photograph of Zay Wilder Walking in the Blackout Ball. In the Kiki Ballroom Scene, Queer Kids of Color Can Be Themselves, The Atlantic, 2015.

Figure 05: Jason, Leeroy. “Performer Winnie Wakanda Washington and ball organiser Treyvone Moo.” The Joburg Ballroom Culture Creating ‘Queer Utopia’, New Frame, 2019.

Figure 06: Daniels, Meghan. Photograph of Cape Town performers Queezy, Daniel Walton, Mziyanda Malgas, and Chester Martinez. A Look Inside Cape Town’s Vogueing Scene, Paper, 2019.

© Alek Tomich_ New York, NY